Shaylyn Martos introduces Dawn Gray, who came to the United States from Honduras when she was 8 years old.

First days, last words

by Shaylyn Martos

How one Honduran woman lost her native language

First days, last words

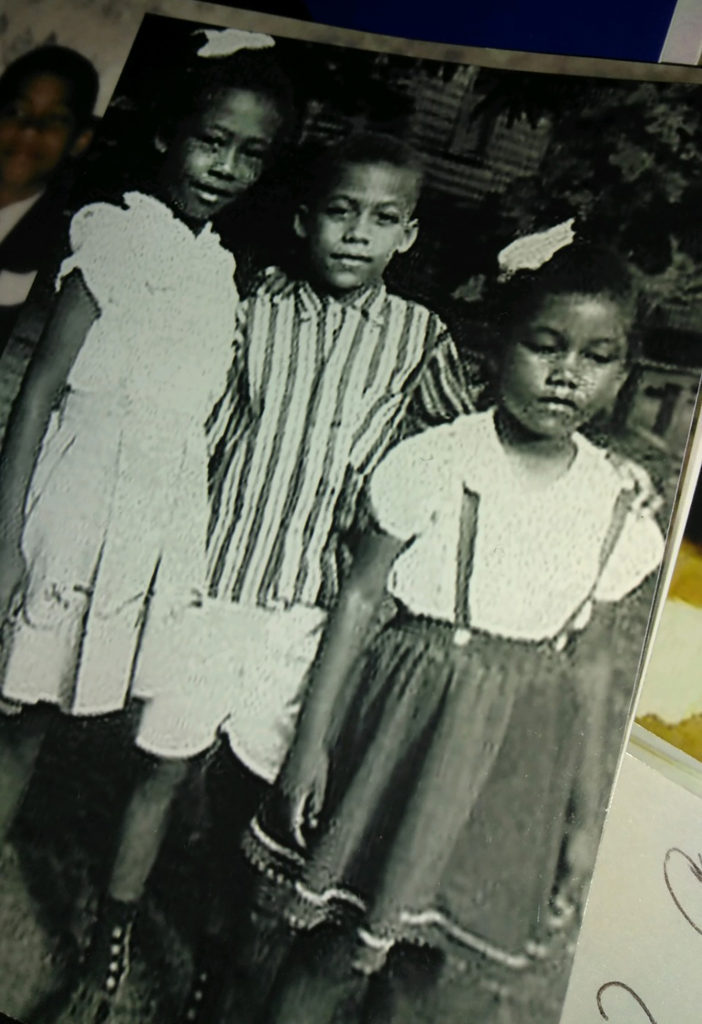

Dawn Gray (left), her brother Saddiq Jihad (middle) and her sister Barbara Henderson (right) dressed in nice clothes for their journey to California from La Lima, Honduras on August 23, 1960. Photo courtesy of Dawn Gray

When Dawn Gray was seven years old, her mother woke her and her six siblings up early, dressed her in a starched blue dress, and told them they were going to see her father. The family boarded a plane in La Lima, Honduras and flew to California.

“My mother had us with these funny socks on, and the little black shoes and the dress with all the little frills on it. I wouldn’t put that on anybody in this day and age,” she said with a laugh. “Oh my gosh, so embarrassing!”

Gray remembers some details of the trip so vividly. Things like the exact date they arrived in Los Angeles: August 23, 1960.

From L.A., they went to San Francisco where Gray recalls crossing a bridge at night into the Bay Area.

“To me, it was beautiful because I hadn’t seen something that exquisite in Honduras,” she said.

Immigrating to America came with a cost. It meant forgetting and leaving some things behind.

When Grey came to the U.S. from Honduras, she lost her ability to speak her native language.

“You’re no longer to speak Spanish to them. They’re to speak English. They’re in an English country.”

Gray remembers her father tell her mother shortly after they arrived, “You’re no longer to speak Spanish to them. They’re to speak English. They’re in an English country.”

Just days after arriving in the U.S., Gray’s father spanked her for the first time because she spoke Spanish. It became clear her father was serious about the family’s assimilation into American culture.

There is no single pattern of language loss for immigrants in the U.S., according to Manuel Pastor, professor of sociology and director of the Center for the Study of Immigrant Integration at the University of Southern California. He said, certain factors do influence language retention for individuals.

“That depends on whether or not it gets spoken in their household, whether or not it gets reinforced in their neighborhood or reinforced in their school,” he said.

Dawn Gray said corporal punishment was not isolated to her home. Her teachers would punish her and her siblings whenever they spoke Spanish in class. They were also teased and pinched by other students.

Even the principal participated in the punishment until one day when her father got involved.

“I got to the office. The principal then spanked me on my hands with a ruler. So, I called my father at work, and that was some serious business,” she said. “He came up to the school and he and the principal had a physical fight.”

Pastor said it was common for people Gray’s age to be physically punished for speaking their native languages in school. It was legal to spank kids in school until California outlawed corporal punishment in the classroom in 1986, many years after Gray and her siblings started school.

“There’s a lot of negative stigma to the language,” Pastor said. “I remember taking Spanish in high school, and deliberately going back and marking a few answers wrong, because it wasn’t a positive thing to be someone who could speak Spanish.”

“I was labeled Black when I came to the United States”

Dawn Gray is a mother, grandmother and great grandmother who came to the United States when she was seven years old. From her first days in California, the adults in her life kept Gray and her siblings from speaking in Spanish. Photo by Shaylyn Martos/NextGenRadio

Race also affected Gray’s experience in the U.S.

“I was labeled Black when I came to the United States,” she said.

Gray doesn’t identify as Black or Latinx, but she recognizes that her family was treated differently once they arrived.

“A lot of people look at you really weird when you’re speaking Spanish and my complexion,” she said. “It’s like, What is she doing? What is she saying? I didn’t have to do that back in Honduras.”

A 2016 article from the Social Policy Report found that Black students are more likely to receive corporal punishment in schools in places where it’s still being used in the U.S. Back then, and even now in some cases.

“There’s a lot of colorism, both in Latin America and of course in the United States as well,” Pastor explained. “And it is the case that people who are lighter skinned, will receive less hostility in the United States, than people who are darker skinned because of the country’s deep and persistent patterns of racism.”

Despite being here since 1960, Gray has never made the jump from permanent resident to naturalized citizen.

“I have not applied for citizenship. I never intend to,” Gray said, “Because of the way the United States treats its people, I don’t want to be a citizen.”

Instead, Gray is working on renewing her green card. It’s a process she must go through every decade.

She has been back to Honduras once, for a couple months when she was about 18 years old. Gray said she didn’t like it because she had adapted to the city life.

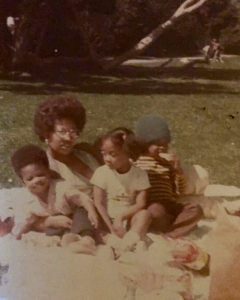

Dawn Gray and three of her children, Donnell Gray (left), Venus Gray (middle) and Lonnie Gray (left), relax in Golden Gate Park in San Francisco in 1975, three years before they moved to Sacramento. Photo courtesy of Dawn Gray

Now two of her six adult children speak Spanish as does one of her siblings, but she refuses.

“I just don’t use it. It is a lot of hurt, we endured a lot growing up,” she said.

But Gray doesn’t regret having immigrated to the U.S.

“It’s worth it for the simple fact that I have my children and my grandchildren and great grandchildren.”

And while she doesn’t speak Spanish, she does cook some meals she remembers from Honduras for her family —one of the only things she kept from her past.